Inflation is a subject that everyone talks about, but few understand.

I thought I would spill some "digital ink" on this topic, not because I fully understand it (anyone that claims to should be met with skepticism), but because I think it's worth exploring how every action can have unintended consequences.

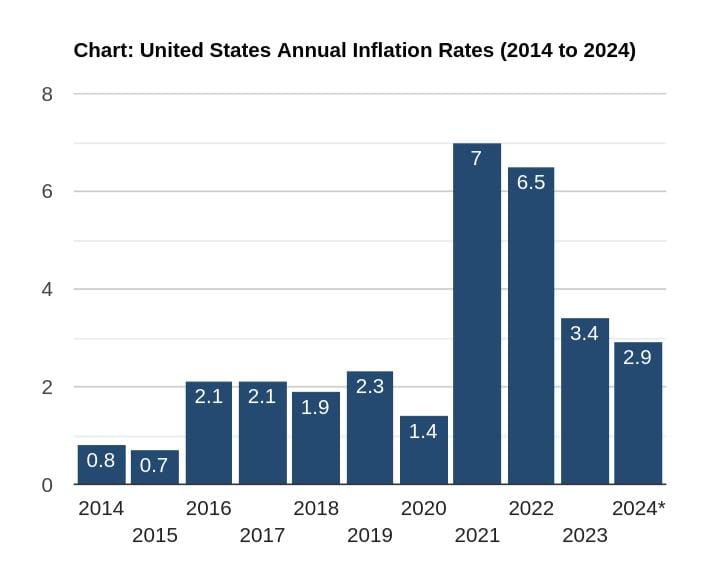

For over two years, the Fed has raised rates at the fastest pace in decades, yet inflation remains above its 2% target. Why? A big part of the answer lies in a phenomenon called fiscal dominance—a situation where the government’s massive debt and deficits undermine the central bank’s ability to control inflation.

At its core, fiscal dominance is about the interplay between government borrowing and monetary policy. When the Fed raises rates to fight inflation, it unintentionally forces the government to borrow even more money to cover its rising interest costs. This additional borrowing injects more cash into the economy, acting as a form of stimulus that keeps inflation alive. It’s a vicious cycle: higher rates lead to more borrowing, which fuels more inflation, which requires even higher rates.

But here’s the twist: even if the Fed cuts rates, the outcome is still stimulative. Lower borrowing costs encourage businesses and consumers to spend and invest more, boosting demand and potentially reigniting inflation.

In this environment, the Fed’s traditional tools for controlling inflation are essentially broken.

I'll try and explain in simple terms how fiscal dominance is driving the stickiness of inflation, why the Fed’s rate hikes haven’t worked as expected, and what this means for investors. By the end, you’ll hopefully understand why inflation is so persistent—and why it’s likely to remain a challenge for years to come.

Let’s start by unpacking the mechanics of fiscal dominance and its role in fueling inflationary pressures.

The Mechanics of Fiscal Dominance

The Debt Problem

The U.S. government is drowning in debt. Here’s the breakdown:

- Debt-to-GDP Ratio: 125%. This means the U.S. owes more than it produces in a year.

- Deficit-to-GDP Ratio: 7%. The government is spending 7% more than it earns annually.

- Government Spending: 25% of GDP. A quarter of the entire economy goes to government outlays.

These numbers are staggering. They mean that the government is not just borrowing to invest in the future—it’s borrowing to pay for today’s expenses, including interest on its existing debt. This brings us to the vicious cycle.

Raising Rates = More Borrowing = Stimulus

When the Federal Reserve raises interest rates to fight inflation, it unintentionally makes matters worse for the government. Here’s how:

- Higher Interest Costs: With $31 trillion in debt, even a small rate hike has a massive impact. For example, a 1% increase in rates adds $310 billion annually to the government’s interest bill.

- More Borrowing: To cover these higher costs, the government must borrow even more money. This additional borrowing injects more cash into the economy, acting as a form of stimulus.

- More Inflation: The extra stimulus keeps demand high, counteracting the Fed’s efforts to slow inflation.

In short, raising rates is stimulative—not because it makes borrowing cheaper, but because it forces the government to borrow more.

Cutting Rates = Cheaper Borrowing = Stimulus

Cutting rates, on the other hand, also stimulates the economy—but in a different way. Lower borrowing costs encourage businesses and consumers to spend and invest more, boosting demand. While this might seem like a good thing, it can also reignite inflation if the economy is already running hot.

The Fed’s Dilemma: No Room to Maneuver

The Fed has already raised rates significantly over the past two years, and many investors expected rate cuts to begin in second-half of 2024. But fiscal dominance has complicated this outlook. Given this vicious cycle, what are the potential solutions? Let’s examine the limited and unappealing options the Fed can take.

1. Negative Real Interest Rates

- Definition: Real interest rates are adjusted for inflation. Negative real rates occur when interest rates are below inflation.

- Implications: This reduces the real value of debt over time but erodes savings and can fuel asset bubbles.

- Challenges: Prolonged negative rates distort financial markets and punish savers.

2. Debt Restructuring

- Definition: Altering the terms of debt, such as extending maturities or reducing principal.

- Implications: Politically explosive and could undermine confidence in U.S. Treasuries.

- Challenges: A loss of trust in U.S. debt could trigger a global financial crisis.

3. Productivity Miracle

- Definition: A sudden, sustained increase in economic productivity from AI or unlimited cheap energy.

- Implications: Could grow the economy faster than debt, but such miracles are rare.

- Challenges: No guarantee that productivity gains will outpace debt growth.

4. Painful Austerity

- Definition: Drastic cuts to government spending, especially entitlements and defense.

- Implications: Would reduce deficits but is politically untenable and could trigger a recession.

- Challenges: Austerity often leads to social unrest and economic contraction.

While these solutions could work, three of them would certainly be political or economic suicide. And one of them is praying for a miracle. That's why I don't think any of them will realistically occur.

Implications for Investors

So what should investors prepare for? Here are the phenomenons worth considering.

1. Inflation Persistence

- With the Fed’s efforts being counteracted, inflation is likely to remain elevated. This should benefit assets such as:

- Commodities (e.g. gold, oil)

- Real Estate

- Inflation-Protected Securities (e.g. TIPS)

2. Higher Volatility

- Fiscal dominance creates uncertainty, leading to market swings. I am preparing for:

- Wider price fluctuations in stocks and bonds.

- Increased hedging costs.

3. Currency Debasement

- Persistent deficits and debt monetization could weaken the U.S. dollar. This benefits:

- Exporters (e.g. multinational corporations)

- Foreign assets (e.g. emerging markets)

4. Higher for Longer Interest Rates

- Despite fiscal dominance, the Fed may still raise or maintain rates to combat inflation. This could hurt:

- Growth stocks (e.g. overvalued or money-losing tech companies)

- Highly leveraged companies (e.g. companies with high debt)

Conclusion: A Paradox Without Easy Answers

Fiscal dominance is a paradox that defies easy solutions. The Fed’s tools are blunted, the government’s debt is spiraling, and inflation remains stubbornly difficult to temper. Whether rates rise or fall, the outcome is stimulative—a reality that will leave policymakers and investors alike grappling with difficult choices.

The question now is not whether fiscal dominance will persist, but how we’ll prepare for a future where the old rules may no longer apply.